Thomson’s Legacy: Relatively Greek

Alexander Greek Thomson Award 2017 - Special Mention

Architecture has long used the analogy of language to

describe a codification of formal gestures or stylistic tropes into a

communicable system of representation for a collective subject. The terms of

this analogy are abstract – form must be intelligible, architectural elements

given symbolic meaning – and it is through this abstraction that a language

begins to be constructed which has a relevance in cultural consciousness.

The classical language of architecture was, until

comparatively recent times, the communicative basis of Western architectural

form. Derived from the classical ideal

of “divine impassibility and beauty residing in pure lines and harmonious

proportions,” this language provided acolytes with the grammatical tools with

which to communicate across historical time, assimilating ideas based on a

correspondence between man, form, and the universe. [1] In

order to be constructive, the principles governing and structuring a language

must be legible to society collectively, not in a deterministic cause and

effect relationship, but in a manner which has the capacity for change and

revision.

For Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, the architect behind some of

the most inventive examples of 19th century architectural

production, the common language was that derived from the ‘eternal laws’ with

which he was concerned: “Some people imagine that the rules of architecture are

arbitrary [...] but the fact is, the laws which govern the universe, whether

aesthetical or physical, are the same which govern architecture. We do not

contrive rules; we discover laws. There is such a thing as architectural

truth.”[2]

Contrary to what this statement might seem to suggest,

Thomson was not dogmatic in his application of the formal laws of antiquity. He was as remarkable for his comprehensive

knowledge of the classical language as for his radical use of it. “The promoters of the Greek Revival,” Thomson

believed, had “failed because they could not see through the material into the

laws upon which that architecture rested. They failed to master their style,

and so became its slaves.”[3]

Through his identification of language as tool, as opposed

to language as doctrine, Thomson gave importance to the structural foundation of

this language upon which mutable form could be conceived, and in doing so,

forged a territory in which formal inventiveness and idiosyncrasies could be

incorporated without departure from an elemental stylistic base. His approach was not historicist. Within his work, overarching laws governing

harmony and proportion are conflated with a pictorial sensibility. As John Maule McKean discusses in his 1985

essay ‘The Architectonics and Ideals of Alexander Thomson,’ “in concentrating

on an ideal, via the abstract, [Thomson] did not see history as a great and

gradually developing tapestry to which he could join. Rather, his more transcendental aim was to use

the data of history to reveal essences […] Thomson was innovating in order to

reinforce the intended illusion.”[4]

In pursuit of the underlying structures of architectural

language, the morphological root of the ideal, it would be easy to render architecture

a cloistered, autonomous, discipline. An

understanding of the evolution of architecture based only on an internal,

disciplinary syntax and the delineation of interests seen as intrinsic to

architecture itself, however, negates the wider socio-cultural and political

context in which any building is conceived and constructed. To formulate this understanding would require

history to be viewed as fragmentary, as a heterogeneous collection of episodes,

a stance which diverges from an account of history composed of models from

which a language could be deciphered.

In his analysis of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s 1794 description

of the Belvedere Torso, Jacques Rancière discusses the formation of an

autonomous history of art as being subject to a historical basis for the

conception of collective life. The

fundamental contingency this engenders becomes critical in developing a

disciplinary autonomy which retains cultural relevance. It is within this relationship, within relative

autonomy, that the idea of legacy is situated.

Rancière describes the convergence of the once fragmentary

histories of objects and ideas from antiquity, uniting the theories of the

ideal and the actuality of the archaeological real into a singular totality. Through bringing these strands together, the

totality is given critical autonomy through the internalised relation of the

objects to each other, with the ideal as interlocutor. Critical autonomy is used here to describe

meaning within this totality; disciplinary autonomy derives meaning in relation

to the other, to the collective. Rancière

employs history as a concept to generate the contingencies required for a disciplinary

autonomy to exist:

“History does not come to take the constituted reality of art as its

object. It constitutes this reality

itself. In order for there to be a

history of art, art must exist as a reality in itself, distinct from the lives

of artists and the histories of monuments […] Yet reciprocally, for art to

exist as the sensible environment for works, history must exist as the form of

intelligence of collective life.”[5]

History, in this context, represents a collective subject. It occupies the realm of shared values, the

public realm, and signifies the commonality between “those who draw the

blueprints for collective buildings, those who cut the stones for those

buildings, those who preside over ceremonies, and those who participate in

them.”[6]

It is inherently a product of its environment

and becomes the intermediary between collectivity and the autonomous space of individual

imagination. It occupies the critical

liminal position.

The reciprocity which is pivotal to this lays plain the

fundamentally dialectical nature of autonomy.

Whilst Rancière’s discussion specifically deals with the history of art,

an understanding of the contingent relationships governing architecture is similarly

significant. To posit an absolute

autonomy of architecture would necessitate dissolving the dialectic we have

just constructed, removing architectural form from its cultural and societal

context. Architecture is a repository

for culture: it holds social memory; it works to bring together iconography and

semiotic issues with material. This most

powerful social aspect of architecture, its capacity to engage with and be

engaged by its context, cannot be excluded in order to form an argument for an

autonomous discipline. Relative autonomy

on the other hand, an autonomy contingent on place and time, on politics and

socio-cultural patterns, on geographical specificities and a global transfer of

knowledge, constructs the framework to bring these divergent issues into a productive

relationship. Considered in relation to

the work of an architect, a building, or an architectural object, this leads to

a far more complex conception of legacy.

The

concept of a formal legacy within architecture is necessarily auto-reflexive.Key

to the relevance of form or element in a time past its initial present is the

understanding of formal legacy as re-presenting objects, as opposed to

presenting artefacts. What distinguishes

the two positions is the nature of the formal.

When considered as object, the formal is relational. Specific to a place and time, the object embodies

the contingencies and inherent ambiguities resulting from its

re-presentation. As artefact, the formal

is conceived as purely self-referential and self-sufficient − the expression of

an internal logic.

Thomson aimed to express an ideal and this is how his legacy

should be thought. Elements from

antiquity are re-presented as objects in their own right rather than as

facsimile or artefacts content with reifying fragments from the past. Andor Gomme and David Walker in their 1968

book The Architecture of Glasgow conclude:

“None of Thomson’s direct successors really knew how to benefit from his

example or to understand what he had done to the remnants of the classical

tradition. Like all great artists who

have inherited a tradition formed into a different context of civilization,

Thomson not only absorbed it into himself but adapted it and reformed it into

something which could once again be a living and expressive medium.”[7]

The amalgamation of the manifold historiographies and social

influences orbiting architectural discourse can never result in a unified

theory or absolute truth. Legacy, as a

result, does not exist within a closed autonomy of form but in the heteronomy

of architectural production and experience. It is intertwined with a temporal

and contextual understanding.

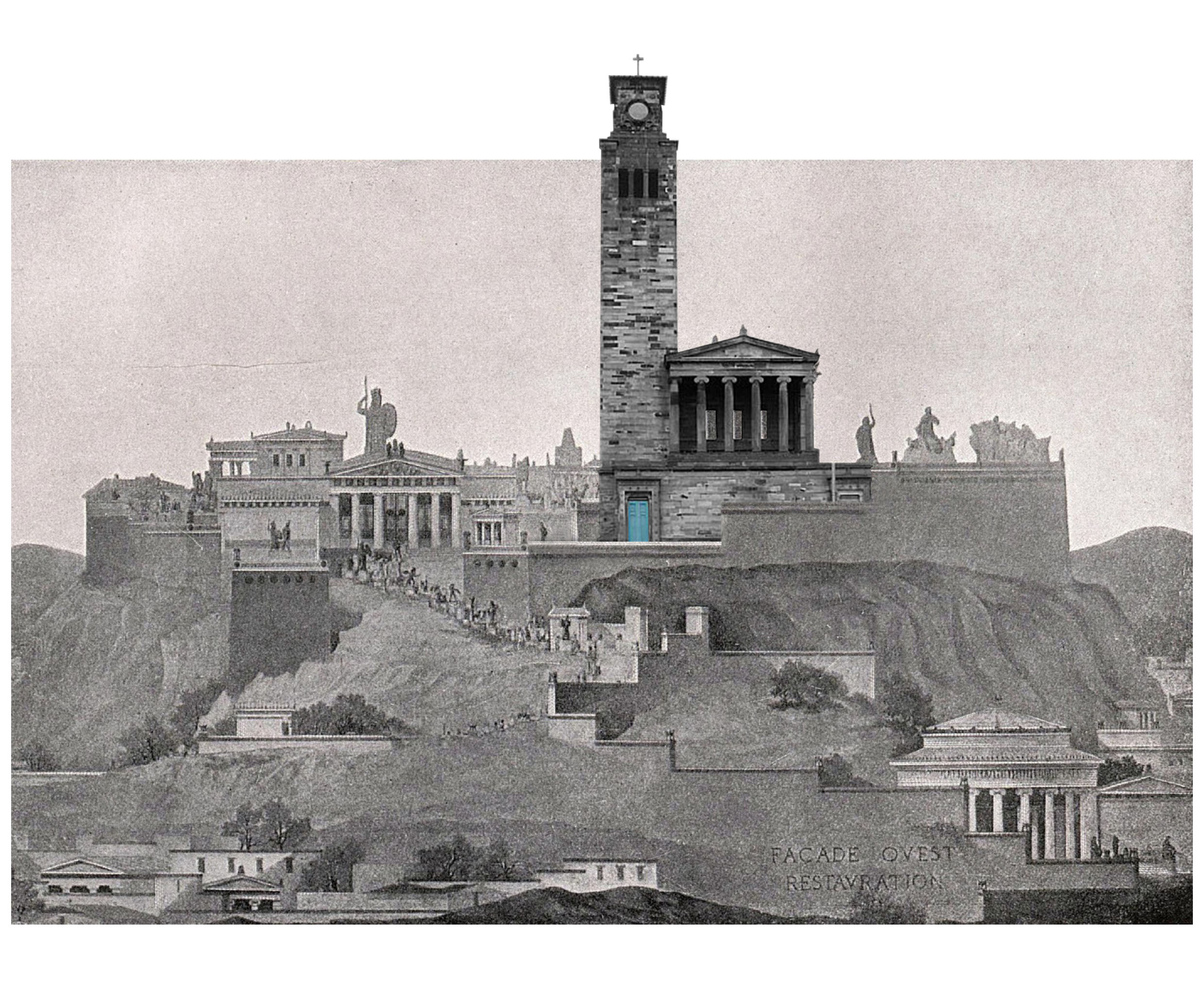

From the banks of the Nile 1500 years BCE and the rocky

hills of Mycenae and Athens a century later, formal legacies have been

transmitted across millennia and continents and have been reimagined for a

different place. Thomson’s radical use of

the language of antiquity combined an articulation and redistribution of its

elements and with a formal inventiveness and revised semiotics befitting his

own time. He produced architecture which

displays an exceptional originality and his buildings have come to act as pivotal

references in their own right. Through

abstraction, not facsimile, but re-presentation.

[1] Rancière, J., Aisthesis (London: Verso, 2013). p.2

[2] Thomson, A., in Stamp, G., The Light of Truth and Beauty (Glasgow: The Alexander Thomson Society, 1999). p.68 [3] Ibid. p.147

[4]McKean, J.M., ‘The Architectonics and Ideals of Alexander Thomson’ in AA Files No. 9(London: AA Publications, 1985). p.32

[5] Rancière, J., Op. Cit., pp. 13-14. The ‘sensible’ for Rancière is the condition of perception, founded on a division of subjectivity that is partly formed within the collective social sphere, and partly by individual experience. [6] Rancière, J., Ibid.

[7] Gomme, A., & Walker D., as quoted in Mordaunt Crook, J., ‘More Thomsonian than Greek’ AA Files No. 9 (London: AA Publications, 1985). p.84